The FCC recently released the particulars—including the minimum opening bid prices and the license locations—for its upcoming 28 GHz and 24 GHz spectrum auctions. And the details are somewhat surprising.

Specifically, the agency’s first auction, for 28 GHz spectrum that starts Nov. 14, will only offer spectrum licenses covering 23.7% of the U.S. population, according to Stephen Wilkus, the CTO at Spectrum Financial Partners. Further, the FCC’s minimum opening bid prices for its 24 GHz spectrum auction are an astounding 188 times lower than the agency’s minimum opening bid prices for its recent 600 MHz spectrum auction per MHz.

Those are the two most interesting data points Wilkus pulled out of the data the FCC recently released about its upcoming spectrum auction. And those data points reflect a number of important elements that wireless network operators and other potential bidders will need to consider as they plot out their auction bidding strategy.

Importantly, the FCC’s planned 28 GHz and 24 GHz spectrum auctions are critical because they represent the first time so-called millimeter wave (mmWave) spectrum will be publicly auctioned. That’s key because the value of mmWave spectrum isn’t yet clear—the best estimate for the value of this spectrum comes from Verizon’s $3.1 billion purchase of Straight Path in 2017. Indeed, that purchase, and Verizon's earlier acquisition of XO, gave Verizon ownership of a big swath of the nation's 28 GHz spectrum, which is a big reason the FCC's upcoming 28 GHz auction isn't nationwide.

And the value of mmWave spectrum (generally spectrum above 20 GHz) is an important factor in the calculations for 5G. Although 5G transmissions will be able to travel through almost any spectrum band (T-Mobile is planning to transmit 5G over 600 MHz) the mmWave bands represent a new battleground for wireless operators because they historically haven’t been used for mobile communications. 5G, however, is changing that.

But mmWave bands are not like other, traditional cellular spectrum bands. Millimeter wave bands generally can only transmit signals relatively short distances—like several hundred meters—whereas traditional midband or low-band cellular spectrum can transmit signals several miles or more, depending on operators’ technologies and spectrum configurations. Further, mmWave spectrum blocks are generally much wider—like 100 MHz wide or more—whereas low- or midband spectrum blocks are typically 10 MHz wide.

Thus, the details of the FCC’s upcoming mmWave spectrum auctions are critical because they will allow carriers like T-Mobile, Sprint, AT&T and others to add additional mmWave holdings to their 5G plans.

And, based on Wilkus’ auction calculations, there won’t be much in 28 GHz to interest most of the nation’s operators. He noted that only 47% of the counties in the United States will offer spectrum licenses in the auction, which equates to roughly 61.7% of the country’s geographic area. Further, Wilkus pointed out that the 28 GHz geographic locations tend to be larger, rural counties, including much of Alaska.

Thus, based on the relatively diminutive propagation characteristics of mmWave spectrum, coupled with the generally rural availability of 28 GHz licenses, there doesn’t look like much quality spectrum that’s going to be made available in November. I’m expecting relatively insignificant action during that auction.

No wonder T-Mobile and others have been pushing the FCC to auction a bunch of mmWave bands—28 GHz, 24 GHz, 37 GHz, 39 GHz and 47 GHz—all at the same time.

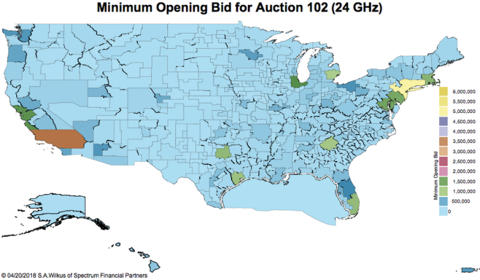

However, the situation might be a little different in the 24 GHz auction that the FCC has scheduled to start shortly after the 28 GHz auction. Wilkus noted that the 24 GHz auction will offer licenses in all 416 Partial Economic Areas (PEAs)—meaning, nationwide. And because of that situation, Wilkus was able to directly compare the opening minimum bids for 24 GHz licenses with the FCC’s recently completed 600 MHz incentive spectrum auction. “We can easily compare their minimum opening bids to past auctions and see that the FCC plans to begin bidding for all 700 MHz of the 24 GHz band at $438 million,” he wrote. “This compares with opening bids for the 600 MHz auction ($1,174 million for each 10 MHz block) in the ratio of 117.4/(438/700)= 187.6 or about 188 times higher opening prices per MHz for 600 MHz spectrum than for 24 GHz spectrum.”

Again, I’m not sure this is all that surprising, considering that the propagation characteristics of 24 GHz are very, very different from 600 MHz.

“We see that even with the larger bandwidths available at mmWave frequencies, the FCC is setting opening bids that are still much less than it has at lower frequencies,” Wilkus said. “For example, the New York PEA opening bid in the 600 MHz band was 26.7 times higher than at 24 GHz even though there was 1/10th the bandwidth. It has been long recognized that mmWaves will be have costly electronics and costly deployment costs that reduce the value of the high frequency spectrum. This is reflected in the low willingness-to-pay estimations made in pricing the auction.”

Even with all this data, though, it’s still difficult to predict exactly how much interest wireless operators and others will actually have in bidding in the FCC’s upcoming 28 GHz and 24 GHz auctions. After all, initial expectations for the FCC’s 600 MHz incentive auction reached as high as $60 billion in total bids but the auction ended up only generating $20 billion in winning bids—and now T-Mobile is the only major wireless network operator that’s actually using 600 MHz spectrum. As Wilkus notes, “we'll have to wait for the auction to discover what the real prices will be.” – Mike | @mikeddano

Article updated April 23 with details on Verizon's XO purchase.