States are getting ready to distribute their Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) funds, with most of the chatter focused on getting low-income communities connected. But new research from Pew indicates there's another group that needs some attention: middle-class families.

In addition to facilitating broadband access for low-income families, Pew pointed out the BEAD program requires that states ensure “high-quality broadband services are available to all middle-class families … at reasonable prices.” However, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) has not set any standard for middle-class affordability, leaving each state to create their own definition of what's "reasonable."

As states work to meet BEAD's middle-class affordability requirements, an initial regulatory challenge will be “potential perceptions of rate regulation,” Pew researchers said. Basically, states will have to balance mandating affordability from providers and avoiding the appearance of rate regulation, considering federal and state governments do not have authority over internet service as they do over utility pricing.

Another challenge is the lack of solid information about how much subscriptions for middle-class families really cost. Internet service providers (ISPs) don't always give complete data about their pricing to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Pew suggested. To address this, it said states and experts should expand affordability research to include middle-income households.

Pew insight on middle-class affordability

With its recent research effort, Pew Charitable Trusts offers states a better look into what might count as affordable internet for middle-class families.

While there isn't one clear standard for middle-class affordability, the FCC in 2016 suggested a basic measure: that broadband shouldn't cost more than 2% of what a household makes each month. Pew’s research leaned on that 2% benchmark to conclude that middle-class household incomes across the U.S. range from $40,000 to $150,000, setting the national median affordability standard of $93.21 (hypothetically).

That standard cost comes out higher than the average plan price reported by other organizations, such as New America which found in 2020 an average nonpromotional price of $83.41 per month. Pew’s standard is lower than the FCC’s reasonable comparability benchmark for 2023, which indicated that an unlimited data plan offering 100/20 Mbps speeds should cost $105.03 per month.

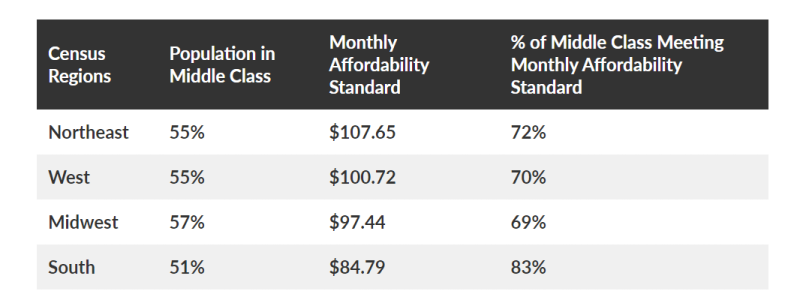

Realistically, a national standard doesn’t account for the fact that affordability varies in different parts of the country. Pew set regional standards as well; in the Northeast ($107.64), the South ($84.79), the Midwest ($97.44) and in the West ($100.72).

Even within states Pew found dramatic differences. The median affordability price for Texas is $92.80 per month, but in its southern Dimmit County the affordable baseline was $41.67, and in the more urban Rockwall County affordability was set at $185.99.

That said, Pew’s research highlighted that because incomes and cost of living vary within regions, not all middle-class households can afford a national 2% benchmark. Considering Pew’s income data, about half of each region’s population would fall into the middle class, but as much as 30% of those middle-class families might not be able to dish out 2% of their income for broadband.

“Millions of Americans could be priced out of home broadband subscriptions, even when affordable plans, as defined by the 2% benchmark, are available,” said Pew researchers. This suggests that state officials “should consider a wide range of potential middle-class incomes when developing this policy."

Ultimately, states should remember that adoption is influenced by various other factors outside of affordability, like network quality, access to service, and digital skills and education, “all of which state officials will need to account for to meet their BEAD obligations and broadband goals,” Pew said.

The research comparing subscription rates and affordability standards across different regions revealed that price doesn't seem directly linked to subscription rates. Even though the Northeast has higher affordability standards, it boasts the highest broadband subscription rates, while the South, with lower affordability standards, has the lowest rates.

Pew researchers concluded: "Understanding what middle-class affordability means—and developing customized, data-driven solutions—for each state and community will be vital to ensuring that BEAD-funded networks make affordable internet access a reality for the millions of Americans nationwide who still lack connectivity."