Verizon is the only major U.S. carrier that doesn’t support the Wi-Fi Alliance’s Passpoint program, which was introduced five years ago in part to allow Wi-Fi users to bypass the hassle of entering a password to get onto a new Wi-Fi network. As a result, Verizon customers aren’t automatically pushed onto Passpoint-capable Wi-Fi networks where they are available.

Verizon didn’t say why it doesn’t support Passpoint, noting in a statement to FierceWireless only that it is “evaluating the use of Hotspot 2.0/Passpoint WiFi technology for future use.”

I suspect that Verizon’s aversion to Passpoint stems from the carrier’s longtime desire to retain direct control over its customers’ network experience. The Wi-Fi Alliance’s Passpoint service essentially allows cellular operators to offload their customers onto Passpoint-capable Wi-Fi networks. While such technology does reduce the amount of traffic on cellular networks and provide connections in locations where cellular might not reach, it also passes the buck from cellular operators to whatever company is operating the Passpoint Wi-Fi network. Companies that operate Passpoint-capable Wi-Fi networks include Charter, Boingo and AT&T.

Thus, Verizon may not want trust other companies to provide good service to its customers.

Further, Verizon has historically been somewhat combative with Wi-Fi. Most notably, the company spearheaded a technology called LTE-U that would allow it to transmit its own LTE signals in the unlicensed spectrum bands favored by Wi-Fi, an action that sparked heated opposition among Wi-Fi proponents until the FCC settled the matter earlier this year. Even a post on Verizon’s website ostensibly detailing the differences between Wi-Fi and cellular technology reads more like a screed against Wi-Fi than a simple tech explainer.

But Verizon is certainly in the minority in its attitude toward Passpoint. All of the other major wireless network operators—T-Mobile, Sprint and AT&T—support the Wi-Fi Alliance’s Passpoint program.

This doesn’t come as much of a surprise though. AT&T acquired Wi-Fi company Wayport in 2008, Sprint inked a major Wi-Fi offloading deal with Boingo in 2015 and T-Mobile quietly tested Passpoint roaming with erstwhile cable operator Bright House Networks in 2015.

The recent Mobile World Congress Americas show, held last month in San Francisco, offered a good snapshot of where Passpoint technology is today. The show was held at Moscone Center, which runs a Wi-Fi network built by Cisco. Boingo tapped into the network to monitor Passpoint usage and found that mobile devices from AT&T, T-Mobile and Sprint were all being pushed onto Moscone’s Passpoint-capable Wi-Fi network.

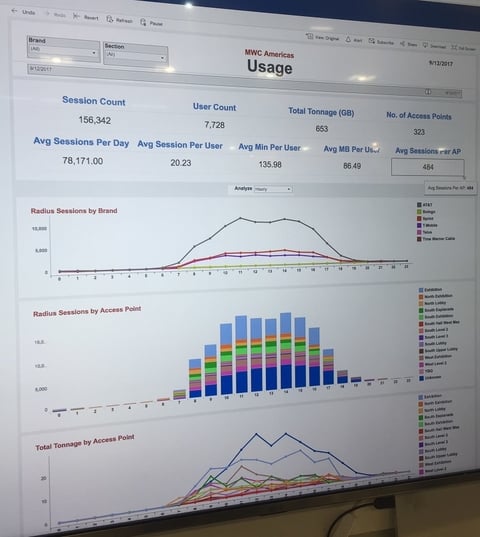

Here’s a picture taken Oct. 13 at the show of real-time Passpoint usage in Moscone Center:

According to the data from Boingo, roughly 7,700 users had accessed the network by that date, sending more than 600 GB of data across more than 300 access points.

“The rollout of Passpoint has been more of a steady rollout,” explained Kevin Robinson, VP of Marketing for the Wi-Fi Alliance. He noted that Passpoint technology is now built into a number of leading operating systems, including Android, iOS and Windows 10. “That’s a pretty significant number of mobile devices.”

Further, he pointed out that Charter, AT&T and other operators are supporting Passpoint from the network side, though he declined to discuss Verizon’s support for the technology specifically. “Passpoint is experiencing steady progress in the market, particularly in that more and more client devices are poised to take advantage of the capability in the network,” he said. “There’s still more work to do in getting Passpoint more prevalent in the network, among operators themselves.”

What’s particularly interesting about Passpoint, I think, is that it paves the way for noncellular companies to provide mobile services. For example, Comcast could blanket downtown Denver with a Passpoint-capable Wi-Fi network, and it could potentially act as a roaming partner for cellular carriers looking to improve their coverage in that area. Indeed, that’s exactly what Sprint’s offloading agreement with Boingo does, which covers dozens of airports in cities across the country where Boingo operates Wi-Fi networks.

But, given the noise around the 3.5 GHz CBRS band, it’s reasonable to wonder whether Passpoint will eventually be supplanted by CBRS. Much like Passpoint, the promise of CBRS (as outlined by the CBRS Alliance) is the ability for venue owners and others to build their own, local LTE networks running in 3.5 GHz spectrum and to provide roaming services to cellular network operators that don’t cover those particular locations.

When questioned about CBRS, the Wi-Fi Alliance’s Robinson took a decidedly defensive position. “Wi-Fi will continue to be a critical piece of operators’ networks. Period,” he said, explaining that the Wi-Fi transmission standard continues to evolve “just as quickly as other technologies out there” with better support for mobility, management and performance.

“We see Wi-Fi as maintaining its lead in delivering the world’s data,” he said.

Interestingly, Verizon’s Ed Chan keynoted a CBRS Alliance event at the MWC Americas show, offering Verizon’s mostly unqualified support for LTE in the 3.5 GHz CBRS band.

So, does that mean Verizon is withholding support for Passpoint in the hopes that something better, like CBRS, comes along? Perhaps. But the underlying question remains: Should wireless carriers offload customers onto networks they don’t directly control, where speeds might slow and services might not work?

Well, first, it’s worth pointing out that this is already happening, regardless of carriers’ attitudes. According to P3, roughly half of Americans’ smartphone data consumption occurs over Wi-Fi, presumably via the Wi-Fi networks at customers’ homes, schools and offices.

And as the data shows, Verizon customers make use of Wi-Fi more often than the customers of other carriers. (P3’s data covers the period before Verizon launched unlimited data, and P3 decided earlier this year to stop providing new data to FierceWireless.) Further, wireless carriers all offload traffic to some degree through roaming agreements, which have been a standard element of wireless services since the dawn of cellular.

Thus, Passpoint is simply a new twist on an old and established concept. And Passpoint isn’t the only Wi-Fi-offloading game in town:

- Google, through its Project Fi MVNO, promises seamless access across 1 million Wi-Fi access points alongside the cellular networks of U.S. Cellular, T-Mobile and Sprint.

- Comcast sells seamless access to its own 18 million Wi-Fi hotspots through its Xfinity Mobile MVNO, which coincidently works on Verizon’s LTE network.

- MVNO Republic Wireless promises cheaper monthly service costs by leveraging nearby Wi-Fi networks.

- Cable operators including Comcast and Charter formed the CableWiFi Alliance in 2013, and last year confirmed the alliance was still up and running, after the industry’s spate of consolidation, with roughly half a million hotspots.

The bottom line here is that the popularity of Wi-Fi stems from the fact that it’s fast, cheap and simple to connect to and install. In the days of 3G and LTE, cellular providers simply couldn’t offer a compelling alternative to the Wi-Fi that customers were already paying for at their home or using at their school or office.

But this scenario may change in the coming years, as unlimited data catches fire among cellular providers while LTE improves and 5G—both fixed and mobile—looms on the horizon. Wi-Fi probably isn’t going anywhere soon, but I think there’s a significant opportunity for cellular players to leverage CBRS and other technologies to make it easier to regular people to deploy LTE and 5G.

But that would also mean that Verizon and other cellular players would have to embrace the notion that they can’t control all of the connections all of the time. – Mike | @mikeddano