At its April, 2022 meeting the Federal Communications Commission is scheduled to consider a Notice of Inquiry into receiver standards — a concept long debated in the industry but on which the Commission has not previously acted. The recent dust-up over C-Band wireless and aviation altimeters — that spilled over into hysterical headlines in the mainstream media — illustrates why such standards are so desperately needed. FCC Commissioner Symington has been a leading voice on this issue. And prominent engineers Dale Hatfield and Pierre de Vries have been evangelists on this topic for years. The views that follow are my own.

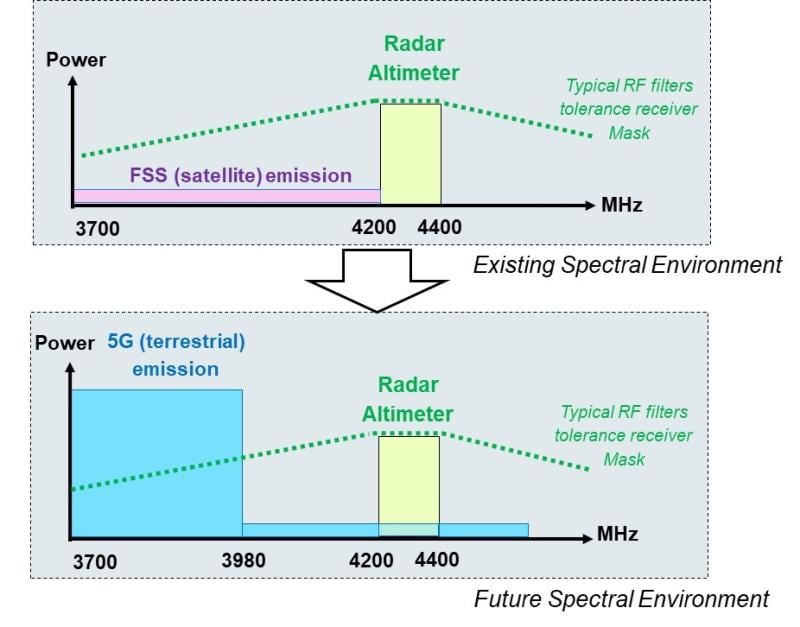

As demand for spectrum grows — seemingly endlessly — it will be necessary to become more efficient in how that spectrum is transmitted and received. Different spectrum users will be packed more tightly without fallow spectrum, or highly specialized/directional users, nearby. In this new world we will not be able to tolerate receiver standards that previously were “good enough” and less expensive to design and build. The two graphs below, submitted in the public record of the FCC by RTCA, illustrate the problem vividly.

Each radio service is assigned specific frequencies by the FCC. In the days of spectrum abundance, receivers did not need to be very selective; they did not need to be designed to receive only their assigned frequencies. To allow for tighter packing of spectrum users, receivers will need to receive their assigned frequencies and reject signals on other frequencies that are, or will be, assigned to other users.

Aircraft altimeters

These graphs depict the receive “mask” — its ability to reject other frequencies — for a typical aircraft altimeter receiver today. They receive signals from a broad band of frequencies — those assigned to altimeters and those assigned to others. As depicted, these sloppy, and less expensive, receivers worked OK in the old days when the only usage of nearby frequencies was from weak satellite signals from space. But when the FCC reassigned some of those other frequencies from satellite transmission to mobile wireless, the inadequate design of the altimeter receivers was exposed — despite a generous 400 MHz guard band!

The key concept here is receiver desensitization and saturation. Receivers have a range of intended signal powers they can receive, from the weakest to the strongest. This is called the dynamic range of a receiver. When you have other power coming into a receiver (e.g. adjacent, or relatively nearby, channel interference) your dynamic range may shrink (i.e. the weakest signal you can receive gets higher). This effect is called receiver desensitization. At some point, you have so much power coming in, you have reached the top of your dynamic range and your receiver is “saturated.” In this condition you cannot receive anything, it’s all too loud, it’s all just noise.

The front-end filter is the most important component for protecting the receiver from frequencies it is NOT licensed to use. You can try to do fancy math to computationally remove and reject interference, but if your filter lets in too much power, and your receiver is saturated, the fancy math can’t save you.

As the FCC starts sharing frequencies more, and repurposing and/or packing more services into sparsely (in geography or frequency or both) used bands, the need for tighter front-end filters (both on Tx and Rx side) is crucial to making it all work.

All of this should have been obvious to the FAA/Airlines starting in 2017, and in the following four years, as C-Band for mobile wireless has been front-and-center industry and general press news. Surely, they knew the shape of their Radio Altimeter front-ends, shown in green in the graphs above, was outdated and underperforming. Surely, they knew the dynamic range and the saturation points of their receivers. It should have been obvious they would have to replace their equipment with receivers using tighter front-end filters to be better prepared to share the band. But somehow, it seems none of that was acted upon. Instead of fixing their own receivers, the aviation industry tried to use regulatory/political pressure to restrict the rights of other spectrum users.

As with other spectrum sharing /new band entrant fights like (Ligado and GPS), the term safety-of-life gets thrown around — planes falling from the sky, farm equipment running amok. Safety often is used as a justification for an incumbent band user to do nothing, keeping their underperforming receivers while demanding the new comers accept onerous rules and limits to ensure the protection of the incumbent. Given the scarcity of our shared spectrum assets, going forward it is important that safety-of-life systems acknowledge that spectrum policy evolution effects all users. They must accept that that outdated and underperforming systems will need to evolve as well. And the FCC will be required to propose and adopt rules setting receiver standards. Good fences make good neighbors!

Preston Padden is the Principal of Boulder Thinking, LLC, a consulting firm. He served as the head of Government Relations for NewsCorp, The Walt Disney Company and The C-Band Alliance.

Industry Voices are opinion columns written by outside contributors—often industry experts or analysts—who are invited to the conversation by FierceWireless staff. They do not necessarily represent the opinions of FierceWireless.